PIC = Pilot In Command

I

struggled in flight school with instrument training and almost didn't make it to graduation because of my poor instrument flying skills.

They say graduating from flight school is really only just your ticket to learn. I'd have to agree. Korea was a great place to exponentially increase your learning as a pilot. I was told that those who got assigned state side (in the Continental U.S.) were lucky to get 200 flight hours a year. I managed to get a total of 500 hours my 1st year in Korea. So, the opportunity to learn was certainly there.

Army Aviation is designed to have an all weather capability. We are required by Army Regulations to file and fly

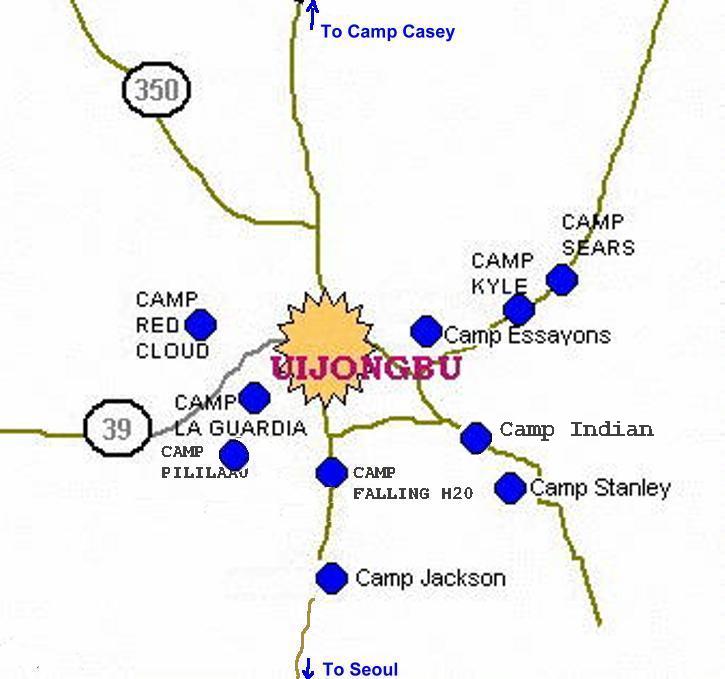

IFR unless doing so would hinder or prevent the mission from being accomplished. North of Seoul, where I was stationed, there is no IFR structure, so 99.9% of all of our flying in Korea was VFR. I'm probably one of the rare few Army pilots who managed to get some actual IFR time while stationed in Korea. Harry told me about getting socked in on the top of a mountain east of Seoul. He called ATC and got himself an IFR clearance and then did an ITO off the mountain, so all weather capability can come in handy when you are where you can utilize it. It can also be dangerous if you are not steeped in the "right stuff".

An ITO is an Instrument Takeoff where the pilot departs the ground and establishes flight solely by reference to the aircraft flight instruments without outside reference.

If you are skilled in the ITO technique, you can depart in zero, zero conditions. The wisdom of this is debated because of the previously mentioned "good idea to always have an out". What if... you have to return for landing shortly after takeoff due to a chip light or something? You usually need a little bit more than zero, zero to land safely. Harry was good to go because clear weather wasn't far off and there were no instrument approaches back to the mountain he was on.

After my 1st year in Korea I was pretty comfortable in the aircraft as far as VFR flying goes. Every Army aviator has to complete an annual instrument checkride to remain on flight status. Even though I did not get any additional instrument flying exposure during my 1st year in Korea having the extra 500 hours in the aircraft did make me more comfortable, and my annual instrument checkride went well. That helped my instrument flying confidence a little.

View Larger MapSoon after passing my instrument checkride I was given a mission to an Air Force Base at the far southern part of South Korea at Gwangju. There was plenty of IFR route structure south of Seoul. I was excited. I would get to practice my instrument flying.

I planned my mission the night before with great detail and was ready.

When I woke up the next morning the weather was absolutely terrible. It was a beautiful day for a good, competent, skilled instrument flyer, which I wasn't. I remembered the warning my last instrument IP gave me when I passed my final instrument checkride in flight school, "Take those clouds seriously. They are nothing to play around in." So, I told myself, "I guess we'll go VFR or Special VFR everywhere today. So much for all that planning."

My copilot that day was a black Lieutenant T.C. Newman. He was a good pilot, but he was green like I had been upon arrival in Korea, fresh out of flight school.

Regardless of flying experience or ability you had to have at least 3 months of flying experience in Korea before you were made a PIC (Pilot in Command). T.C. had not yet hit the 3 month mark.

All the men I flew with when I was green took good care of me and groomed me to excel in Korea, but all the flying we did was VFR. I did not have the opportunity to build any quality experience with seasoned guys in the IFR realm of flight. I did have plenty of marginal VFR flying experience. This mission would be covering plenty of territory, especially once I got south of Kunsun, that I had no experience flying in VFR or otherwise.

T.C. and I did our preflight and soon departed

Uijeongbu for

Osan AFB to pickup our PAX which were a few American Army Officers and a Korean General.

We crept into Osan on a special VFR clearance picked up our PAX and departed on a special VFR clearance heading for

Kunsan AFB.

We made it into Kunsan with a special VFR clearance also. At Kunsan we refueled. One of the American Officers tried to talk me into using the weather as an excuse to RON (Remain Over Night). He mentioned something about knowing a

WAF at Kunsan. My work ethic caused me to decline and press on to complete our current mission.

We departed Kunsan on a special VFR clearance in route to

Kwangju AFB.

I had been into Kunsan before, but everything south of Kunsan was new territory for me. As mentioned in previous marginal weather flying posts I talked about how familiarity of your AO (Area Operations) helps. Besides being new territory to me, I could feel the weather getting worse. Besides simply getting worse it was quickly going to the point where VFR flight would no longer be possible. I had all of my instrument flight preparations with me, but I had no confidence in my ability to pull off the flying part. I had to do something though, because soon the weather would force us on the ground.

I wondered how T.C. did in instruments, so I asked, "T.C. how'd you do in instruments?"

He came back with, "I did good."

That's all the vetting he had for my next decision, "Kunsan departure control. Tomahawk 1234 requesting IFR to Kwangju."

Departure control replied, "Tomahawk 1234 Roger. Climb to and maintain 8,000 feet."

I pulled pitch to climb and we soon entered the soup. I worked on getting my crosscheck to lock in. I wallowed 30 degrees left then 30 degrees right. My crosscheck wasn't coming in. Besides that Kunsan gave us instructions involving equipment we didn't have, e.g.

DME etc.

I'd respond, "Tomahawk 1234, negative DME"

Finally they told us to just track to the Kwangju

NDB.

After struggling to get my instrument crosscheck to lock in without success, I decided to give T.C. the controls to see what he could do.

I said, "T.C. you have the controls."

T.C. responded as he took the controls, "Roger. I have the controls."

Fortunately TC's instrument skills were better than mine. He wallowed a little bit initially, but not as bad as I did. Before he smoothed out his crosscheck I thought to myself, "Oh boy, ROWBEAR , what kind of trouble did you get yourself into now. Come on T.C. lock it in!" And he did. His crosscheck smoothed out nicely. If it hadn't, this decision of mine might not have turned out good.

I let T.C. fly a little longer before I decided to give it another try. Finally I said, "Okay T.C. I have the controls."

He visually affirmed I had them before releasing them and saying, "Roger. You have the controls."

My crosscheck locked in! Thank God! I smoothed out. After remaining on the controls long enough to make sure it was real and to feel comfortable. I handed the controls back to T.C. When he received them smooth, he remained smooth.

One of the American Officers in the back who was also an aviator told me later instruments can be a little rusty sometimes. He also said that as we climbed through 7,000 feet a big sucker hole opened up, and the Korean General unbuckled his seatbelt, stood up, and pointed to the ground as if to say, we should land.

With the flight experience I have and the things I've seen, when someone learns I'm a pilot and invites me to go flying with them, I'm not too keen on the idea especially if I don't have access to the controls and familiarity with the aircraft. I can only imagine what it felt like in the back of that aircraft when we pulled up into the clouds and started wallowing 30 degrees left and right as we climbed.

Once T.C. and I both smoothed out, the rest of the flight was fun and uneventful. We were still at a pretty high altitude when T.C. caught sight of the Kwangju airfield and told the controller, "Airfield in sight". I would have preferred practicing the approach to a lower altitude. But, we made it.

The American Officers invited us to join them at the club, but I declined since I knew tomorrow would also be a big day knowing the smarter thing to do would be to get a good night's rest.

One of the American Army Officers told us the next day that the Air Force Officers in the club wanted to know where the junior fly boys were that flew that helicopter in there in that kind of weather.

I would have only one more for real IFR flying experience in Korea that is another story in another way. The instrument flying all went well with this other story and my copilot and I were both glad to get home due to the instrument option.

One of my buddies in Korea later went to the Instrument Examiner school at Fort Rucker while I was instructing Contact, Tactics, NOE, Nighthawk, and NVG. He talked me into being his student pilot. That ended in disaster. Fortunately not a crashing disaster.

I wouldn't become truly comfortable and competent with instrument flight until I became a contract instrument instructor pilot back at Fort Rucker. I'm sure that job experience helped me to survive the IIMC experience I had in the post:

178 seconds to live.

In my post:

Marathon HEMS Shift I mentioned the July 2010 issue of Popular Mechanics article "Why Medical Helicopters Keep Crashing". This article offers solutions. It is a long and complicated subject. There are detractors and "devil's advocates" on all sides of the issue even what I think would be the optimum best improvement to increase HEMS safety. And, that would be an apprenticeship portal company possibly government subsidized that operates dual pilot, all weather, with no autopilots that all pilots interested in moving into the Helicopter Air Ambulance sector of flying would have to pass through to become certified for single pilot HEMS operations. Like the 3 months minimum time in country to become a PIC, these men or women would need a certain amount of time and exposure to different flight experiences while flying with experienced pilots that have already been there and done that before getting signed off as able to be a qualified HEMS pilot. But then in this world we are often faced with "the way it is" and "the way it ought to be". Rarely do the two coincide.

There you have it! Another Tall Tale I'm grateful to have survived.

Ciao...